Big Questions in Citizen Science

By Sarah M. Dunifon

April is citizen science month and as an informal STEM education evaluator, a former informal STEM educator, and a current STEM hobbyist, I'm all about getting regular people engaged with scientific knowledge.

Early in my career, I had the pleasure of working with the Urban Wildlife Institute at Lincoln Park Zoo, educating Chicagoans on urban wildlife and how they can be a part of collecting and making meaning of ecological data.

Since then, I've worked with a number of citizen science-aligned organizations as an evaluator and science communicator. I've also dabbled as a citizen scientist myself, contributing to projects like iNaturalist, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and National Audubon Society's Great Backyard Bird Count.

Citizen science is used to describe scientific projects that crowdsource the collection or analysis of data with members of the public (non-scientific community). Sometimes citizen science includes non-scientists in the development of a research study as well. It is a form of informal learning since it typically takes place outside a traditional educational setting.

Citizen science is valuable not only for collecting and analyzing large amounts of data quickly but also for growing the scientific literacy and interest in scientific issues of the public.

Now, you might have heard some conversation about the different terminology associated with this type of work. Terms like citizen science, community science, participatory science, and crowdsourced science all convey similar messages but are chosen for distinct purposes. The original term citizen science, coined in the 1990s, has come under criticism for its perceived exclusionary messages. Terms like “citizen” and even “science” can send subliminal messages about who is welcome in this type of work. For that reason, the rise of terms like community science and crowdsourced science attempt to be more inclusive and welcoming to everyone. For the purposes of this blog post, we’ll stick with citizen science as it is still the most widely accepted term, although it is important to recognize the limitations it poses.

Researching for this newsletter gave me a chance to reconnect with some citizen science projects I’ve long admired or participated in myself! Personally, I’ve contributed to the Great Backyard Bird Count, BioBlitzes, and iNaturalist. This piece inspired me to re-engage with iNaturalist and log a grub I recently found in my garden.

iNaturalist entry page

Other examples of citizen science projects include:

And these are just a few of the thousands of citizen science projects in operation. To learn more about citizen science and to find a project, check out these resources:

Beyond the benefits of citizen science to the scientific community, research recognizes individual benefits of participating in citizen science, including increasing scientific knowledge and literacy, developing a better understanding of the process of science, and developing positive action on behalf of the environment (Phillips et al., 2018). Yet many citizen science initiatives do not have well-defined learning outcomes or systems of measurement in place.

There are so many exciting questions we can ask about citizen science. If you’re running a citizen science project, you may want to think about the specific outcomes of that project, not only for the scientific community but for the volunteers themselves. Questions you consider might include:

Why do citizen scientists choose to contribute their time to this project?

What do volunteers learn as a result of their participation in this project?

Does participating in this citizen science project grow volunteer interest in science?

Does participating change how volunteers see themselves? For example, do they see themselves more as scientists after participating? Does it increase their sense of identity, self-efficacy, or belonging in STEM?

Folks are also interested in learning more about how citizen science as a whole contributes to various impacts and outcomes on our community. Questions we might think about include:

How successful are citizen science efforts in democratizing STEM? Does citizen science offer folks usually excluded from scientific circles a chance to engage with STEM?

What is the overall impact of volunteer citizen scientists on the scientific community or on our collective scientific knowledge?

And researchers are learning some really interesting things. As Bruckermann et al. (2019) note, citizen science typically is not designed to put the learning of volunteers first. Rather, most citizen science projects are designed to collect, clean, or analyze large swatches of data. With this science-first approach, learning outcomes for volunteers are often left out of the conversation.

Bruckerman et al. (2019) also learned some key things about how educators can design citizen science projects to best connect with their audiences:

“Specifically, we found that the ways that facilitators framed the activities and positioned young people at CS events like BioBlitzes greatly influenced whether and how young people took on roles in CS practices.”

“Educators who are experienced to work with a particular age group in out-of-school settings are more likely to meet children’s needs (e.g. to make fun) than scientists or formal teachers.”

The educational framing of the citizen science experience is really important in imparting greater outcomes to youth. So, scientists and other STEM professionals should make concerted efforts to partner with educators (especially informal educators) in designing their projects.

Bruckermann et al. (2019) also found that students want to feel “appreciated, valued and trusted for the work they contribute” and that they feel disappointed if the researchers are now able to answer research questions at the end of the study. They also found that students need to see the connections between citizen science work and their daily lives - relevance.

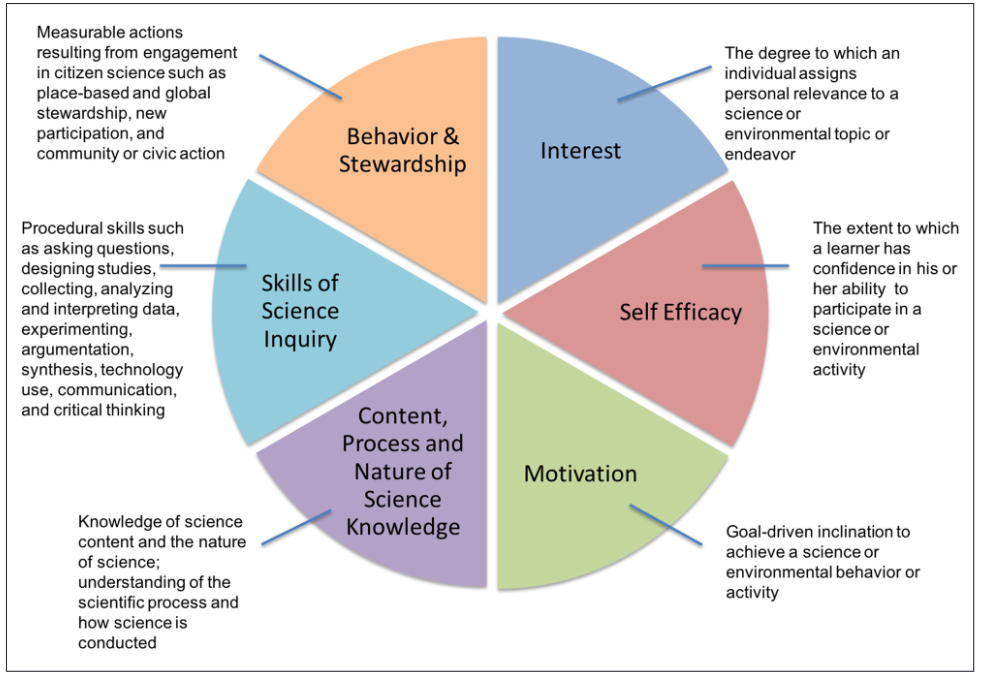

But what about the citizen science projects still struggling to define and measure learning outcomes? They can reference the Framework for Articulating and Measuring Individual Learning Outcomes from Participation in Citizen Science, designed by Phillips et al. (2018), which describes common areas of inquiry:

Framework for Articulating and Measuring Individual Learning Outcomes from Participation in Citizen Science, designed by Phillips et al. (2018)

References:

Bruckermann, T., Lorke, J., Rafolt, S., Scheuch, M., Aristeidou, M., Ballard, H., Bardy-Durchhalter, M., Carli, E., Herodotou, C., Kelemen-Finan, J., Robinson, L., Swanson, R., Winter, S., and Kapelari, S. (2019, August 26-30). Learning opportunities and outcomes in citizen science: A heuristic model for design and evaluation. European Science Education Research Association, Bologna, Italy. https://www.esera.org/publications/esera-conference-proceedings/esera-2019

Phillips, T., Porticella, N., Constas, M., & Bonney, R. (2018) A framework for articulating and measuring individual learning outcomes from participation in citizen science. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 3(2): 3, pp. 1-19.

---

Follow along with Improved Insights by signing up for our monthly newsletter. Subscribers get first access to our blog posts and our 60-Second Suggestions. Join us!